6.1Miriam Devlin

Exceptional, Typical, Chairs by Dick Poynor

Richard “Dick” Poynor, who lived from 1802 to 1882, made these slat-back post-and-rung chairs (Figure 1) and many others like them. His well-practiced, simple, and light design language and tidy craftwork are recognized by a growing number of collectors and museums.1 His chairs can be distinguished by their lathe-turned legs and back posts, which are curved backward to support good lumbar posture, shaved flat above the seat, and carved into rounded mule ears at the tops. The back slats are pegged in place with a visible pin through the top slat. The joinery of the rungs is hidden, and no Poynor chair has been recorded to come apart at these seams. His chairs often make use of maple for the posts, hickory for the rungs, and split oak for the woven seat.

Although Poynor was a prolific maker, only scant oral history and the woodwork—including hundreds of chairs—remain as record of his processes. Scant details, such as that he is known to have used a horse-powered lathe in his chair factory, have been written into the record from oral history.2 His chairs are both exceptional, in their longevity and pleasant composition, and typical, in that they are stylistically and functionally similar to chairs made by many other chairmakers. To support this duality, I studied the lineages of craftspeople, functional design, and lifestyle that Poynor’s chairs, and his life circumstances, represent.

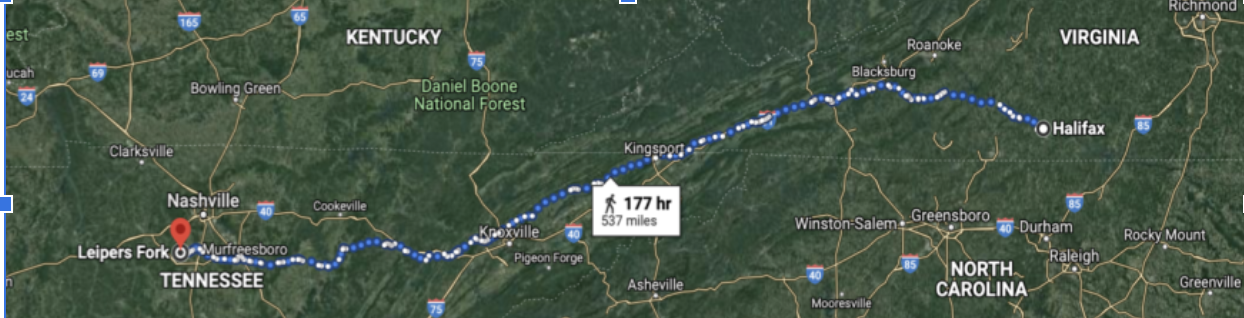

Poynor was born enslaved in 1802, in Halifax, Virginia, to Robert Poynor, who likely taught him the trade of chairmaking.3 In 1816, Robert, with his family and a retinue of enslaved laborers (children and adults, fractured segments of families), moved to Leiper’s Fork, Tennessee, where they continued farming tobacco and cotton, doing masonry work, and making chairs.4

To these settlers, Tennessee was “the backcountry,” and migration to the area meant homesteading to reproduce the plantation lifestyle that previous generations had established in Virginia and North Carolina, using methods which had farmed the soil there to a state of nutrient depletion.5 In this way, families tried to “re-create and perpetuate networks of friendship and extended family in their new backcountry homes.”6 These settlers migrated to Tennessee for the resources, hardwood timber, and good soil, and kept in close contact with family near and far (Figure 2).

Historian Lisa Tolbert has written extensively about Tennessee and the town of Franklin around the time of Poynor’s life. In “Henry, A Slave, v. State of Tennessee,” she writes that the line between free and enslaved was more porous for African Americans living in Franklin in the 1850s than it was for African Americans living on either plantations or in truly rural areas, as enslaved people in the Franklin area often worked for wages and had some personal freedoms. This kind of freedom enabled Poynor to make and sell chairs even while still enslaved to Robert, and to use the proceeds to purchase his freedom and that of his second wife, Millie.7 They established a home on Pinewood Road, nearby to Robert’s plantation and across the street from another Poynor family. That no written record has been found of this transaction is in line with Tolbert’s finding of the legal laxity of these arrangements at that time. I found records that Poynor’s children worked for more than one family of “white” Poynors, as well as other “white” planters, and were bought, sold, willed between generations, and served a variety of professional appointments in the region up to and after the time of his self-emancipation.8

These three newspaper images (Figure 3 - not reproduced, permission pending) represent the majority of print documents from the time of Poynor’s life which I was able to find and which mention him by name.9 I could find no record of Poynor’s emancipation, but the date has been noted as being between 1850 and 1860.10 In the advertisement “CHAIRS! CHAIRS!” which he placed for the sale of chairs in 1849, he claims himself to be “now ‘on my own hook,’” which establishes an earlier date of emancipation than I have found elsewhere. Poynor died soon after the second message expressing concern about his health was sent in 1882. In Poynor’s obituary, he is referred to as “one of the best-known citizens of old Williamson, and was honored by all who knew him, though a colored man.” The inclusion of “though” in the wording of his obituary seems to imply that it was written by and printed for a “white” audience, whereas the second part of the clause states that Poynor commanded “the respect of all,” indicating a wider audience.

There are records of plantation- and slave-owning “white” settlers named Poynor living in the 1800s in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky, and at least four “white” Poynor families in Williamson County itself. Much has been written about their personal histories.11 Records of the enslaved African American Poynors are lacking. Significant work has been done to connect genealogies to living relatives by Williamson County public historian Thelma Battle. Most of Poynor’s descendants now use Poynter as their surname, and live outside the Williamson County area. (Figure 4 - not reproduced, permission pending)12 In Blacks and Tennessee, Lester C. Lamon writes, “Black fears for the preservation of the family … were firmly grounded in experience,” and “ancestral naming patterns and oral traditions became protective devices.”13 More information exists, in the form of oral history, family stories, personal archives, and photographs, about the family networks and heritages of Poynor’s family than I have been able to access. By contrast, I have been able to more easily explore the history of the design of Poynor’s chairs, as this history is available in writing in the academic record, and because the woodwork has lasted well.

There was a period of about 40 years, starting in the decade before the Union occupation of Franklin in 1864, when it was viable for African American families to live on and work the land while living free in the Middle Tennessee area—and they did.14 Over the course of the 1900s this changed, as Confederate-sympathizing locals reacted to emancipation violently and with prejudice, and African Americans in the area lost their land and moved away. The region is now renowned for its conservative values, and Williamson is the wealthiest county in Tennessee.15 Tori Keafer reported for the Williamson Herald in April of 2021 on the affordable housing “crisis” in Franklin, in response to the closing of yet another trailer park.16 Jill Lawrence, on racial relationships and understanding in modern day Franklin, wrote that “the town had more blacks than whites at the time of the Civil War. They were plantation slaves. By 1990, Franklin was only 14 percent Black, and in 2000, as whites flooded into the area, the Black population was down to 10 percent.”17

Chairs of a similar style and build to Poynor’s were made, it seems, in every valley in Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina. Williamson County public historian Rick Warwick refers to the larger area as “teeming with homemade chairs.”18 Along the scattered paths of migration these settlers traveled, generations of families in the region practiced subsistence crafts like chairmaking to outfit their own spaces as well as to sell. The same styles can be found in all the areas settlers migrated through. (Figure 5)

While the basics are similar from chair to chair, the details vary widely. The ratios of each section to another, precise methods of joinery, and the shapes of the turned posts and rungs are all compositional specificities. These nuances define the work of an individual maker, hint at that maker’s lineage, and, with careful examination, can be tied in perpetuity to an individual as their creator.19 Poynor’s chairs differ from one another in the finish of the surfaces of the wood and in their ornateness, but his chairs are never rough, rustic, or rickety; many, if not most, of the chairs made by others in a similar style in the region are one or all three of these.

A long history of chair scholarship has tracked chairs of this general form, called post-and-rung, back centuries to Western Europe (Figure 6), where migration carried the basic design across fluctuating borders, much as methods traveled through expanding communities settled in the US in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The painting from sixteenth-century Germany shows a carved post-and-rung chair. These more rustic chairs, which were produced in New Jersey at the end of the eighteenth century, are made with staves and square-edged wood stock, and the mortises (or holes) are bored all the way through the vertical posts to capture the rungs. In this chair, the staves are shaped by shaving, which makes for stock that more closely follows the grain of the wood. Turning the posts into perfect cylinders on a lathe, as Poynor did, is a further step of refinement that requires a machine, and which works best with carefully selected, straight-grained wood.20

Historian Rick Warwick has been studying Poynor’s chairs for decades. Much of what I have been able to learn about Poynor’s chairs, I have found in his work. Warwick has made note of the fact that he has never encountered a chair of Poynor’s where one of the connections between post and rung has failed, and the joint did not come apart even when he used a car jack to try to break it.21

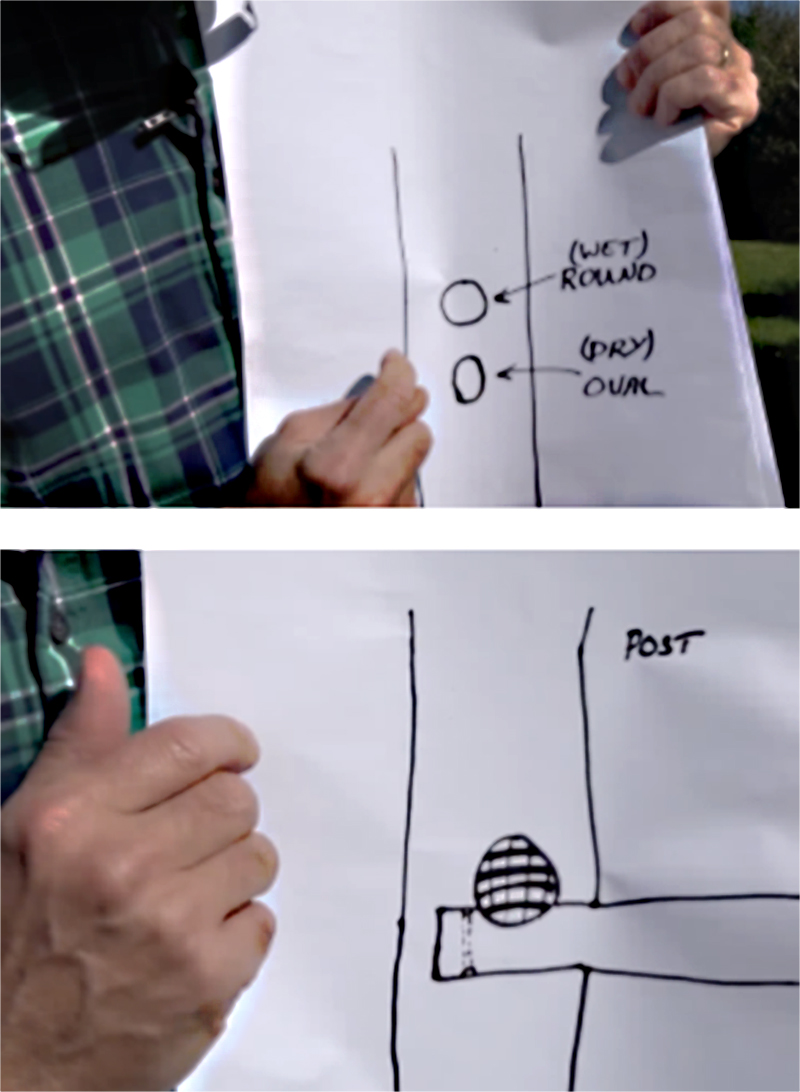

Warwick’s speculations about the chair’s joinery and fabrication processes led me to research green woodworking, and I found that there has been a revival of these methods, led by green woodworkers Jennie Alexander and Peter Follansbee, over the past 20 years.22 In Alexander’s method, the leg posts, front and back, are carved from green wood, and the rungs are heat-dried, cured, and hardened after shaping. The chair is assembled while the posts are still wet, and so the mortise into which the rungs fit shrinks as the wood dries, permanently capturing the rungs. This is the same mechanism for fastening chairs together that Warwick describes Poynor as having used. The rungs on a well-made chair like this also interlock with each other in the joint, at right angles captured in the green wood (Figure 7). There are now many modern makers producing Alexander’s design, which is styled differently than Poynor’s chairs, but uses the same reliable, expert, joinery methods.

Poynor made chairs that were exceptional. Their longevity and growing value as antiques are a testament to their durability and simple elegance. All the more impressive: even though he worked using standard conventions and styles for his region and era, and lived a life well-connected to many in the wider region, with neighbors who spent their time in very similar ways to how he spent his, Poynor’s chairs still manage to stand out. The design of these chairs was not an innovation, but they are excellently crafted with recognizable character. Although little has been recorded about the personal details of his life, much remains of his work, and of the respect it garnered.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Jennie, Peter Follansbee, and Robert F. Trent. “Early American Shaved Post-and-Rung Chairs.” American Furniture (2008). Accessed October 16, 2021. http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/581/American-Furniture-2008/Early-American-Shaved-Post-and-Rung-Chairs.

- Bell, Michael W. “‘First Rate & Fashionable’: Handmade Nineteenth Century Furniture at the Tennessee State Museum.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 62, no. 1 (2003): 5–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42628520.

- “Coming and Going” African American Photo Exhibit (2015). WC-TV, February 23, 2015. Accessed October 4, 2021. http://archive.org/details/Coming_and_Going_African-American_Photo_Exhibit_2015.

- Federal Register. “Notice of Inventory Completion: Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Division of Archaeology, Nashville, TN,” August 3, 2010. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2010/08/03/2010-18991/notice-of-inventory-completion-tennessee-department-of-environment-and-conservation-division-of.

- Jones, Tina Calahan. “William Holmes - Company A, 5th Massachusetts Cavalry Veteran.” From Slaves to Soldiers and Beyond - Williamson County, Tennessee’s African American History (blog), April 29, 2017. http://usctwillcotn.blogspot.com/2017/04/.

- Keafer, Tori. “FrankTown Draws Attention to ‘Housing Crisis’ in Franklin.” Williamson Herald, April 22, 2021. http://www.williamsonherald.com/communities/franktown-draws-attention-to-housing-crisis-in-franklin/article_6ef27c90-a3ab-11eb-abec-4bd38edc1564.html.

- Lamon, Lester C. Blacks in Tennessee, 1791–1970. Knoxville: Tennessee Three Star Books, published in cooperation with the Tennessee Historical Commission [by] the University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

- “The Land and Native People | A History of Tennessee Student Edition.” Tennessee State Library and Archives Education Outreach Program. Accessed November 1, 2021, https://tnsoshistory.com/chapter1.

- Lawrence, Jill. “Values, Points of View Separate Towns — and Nation,” USA Today, February 18, 2002. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2002/02/18/divided-nation.html; https://www.geocities.ws/queermontclair/QMNewsletter202.html.

- Long, Creston S. “Southern Routes: Family Migration and the Eighteenth-Century Southern Backcountry.” PhD diss., College of William & Mary – Arts & Sciences, 2002.

- Ormsbee, Thomas Hamilton. “Flashback: Slat-Back Chairs in Europe and America.” Collectors Weekly, March 20, 2009. Accessed October 16, 2021. https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/slat-back-chairs-in-europe-and-america.

- Poynor, Frank. “John Poynor, Father of John Smith Poynor.” Williamson County Historical Society Journal, no. 22 (Spring 1991): 31–33.

- Robinson, Carole. “African American Local History in Photos Displayed at Library.” Williamson Herald, February 3, 2016. Accessed October 17, 2021. http://www.williamsonherald.com/features/w_life/african-american-local-history-in-photos-displayed-at-library/article_04368054-cb02-11e5-832d-a3e1608fc75f.html.

- Tolbert, Lisa. “Henry, A Slave, v. State of Tennessee: The Public and Private Space of Slaves in a Small Town.” In Slavery in the City: Architecture and Landscapes of Urban Slavery in North America, edited by Clifton Ellis and Rebecca Ginsburg, 142-154. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2017.

- Warwick, Richard. “A Century of Chairmakers 1850–1950.” Williamson County Historical Society Journal, no. 22 (Spring 1991): 8–30.

- Warwick, Rick. “Williamson County in Black & White.” Williamson County Historical Society Journal, no. 31 (2000).

- “Warwick to Present on Historic Poynor Chairs at Brentwood Library.” Williamson Herald, August 23, 2016. Accessed November 1, 2021, http://www.williamsonherald.com/features/entertainment/warwick-to-present-on-historic-poynor-chairs-at-brentwood-library/article_9469e60e-692f-11e6-bd4b-63c4ee38950b.html.

1. Poynor chairs are noted as easy to find for $1 in the 70s, whereas in a recent auction a pair sold for $2,400. See Rick Warwick in The Highland Woodworker - Episode 29, accessed November 1, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qw0BpunBLsQ. There is record of the spelling of Poynor as both Poyner and Poynor. I am spelling it Poynor, which is the spelling most often used by the Williamson County Historical Society, whom I credit for archiving and publishing much on the life and times of Dick Poynor.2. Michael W. Bell, “‘First Rate & Fashionable’: Handmade Nineteenth Century Furniture at the Tennessee State Museum,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 62, no. 1 (2003).3. In The Highland Woodworker - Episode 29, Rick Warwick alludes to Robert being Poynor’s father, though little exists in the way of records to support this assumption. Poynor is described as “mulatto” on the historical marker placed on the land that was his home, and in Bell’s “‘First Rate & Fashionable,’” 42.4. Leiper’s Fork is an unincorporated township of the small city of Franklin, in Williamson County, outside of Nashville, Tennessee. Frank Poynor, “John Poynor, Father of John Smith Poynor,” Williamson County Historical Society Journal no. 22 (Spring 1991): 31–33.5.In the 1800s when settlers were moving into what is now the Williamson County area, there would still have been nomadic communities of native peoples moving through the area seasonally, and they did have some interaction (“white settlers began to wrest the area from the Indians,” in “Williamson County,” Tennessee Encyclopedia Online). Disease and violent displacement by explorers from Spain in the 1400s caused societal collapse, and the migratory tribes present in the 1800s were in the area after having been displaced from elsewhere. Oral histories and archaeological findings from the surrounding area date settled civilizations of indigenous peoples in the area back to the year ~1000 (“A History of Tennessee Student Edition Online” and “Notice of Inventory Completion: Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Division of Archaeology, Nashville, TN,” 2010).6. Creston S. Long, “Southern Routes: Family Migration and the Eighteenth-Century Southern Backcountry” (PhD diss., College of William & Mary – Arts & Sciences, 2002), https://scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3202&context=etd.7. Rick Warwick, “Williamson County in Black and White,” Williamson County Historical Society Journal, no. 31 (2000).8. I have “white” in scare quotes in this paper because scholarship about race has reached a point (at the time of this writing) where it is well-supported and understood that “white” is a constructed identity. Robert P. Baird wrote a summary of the history of the idea of the construction of whiteness for the Guardian in 2021 in an article titled “The Invention of Whiteness: The Long History of a Dangerous Idea.” “White” families and the Black families who they enslaved were often, or even usually, direct relatives—the literature I cite about these communities in this paper treat “white” and Black people as definitionally separate. These scare quotes are a way to acknowledge both that this is an outdated and unrealistic albeit meaningful and significant division which continues to dictate very real outcomes, and that while it is beyond the scope of this paper to dissect the matter, I felt it necessary to include some indication that the issue is more complex than the language here used belies.9. There are at least four estate documents, not pictured, which note Poynor and his family members as possessions.10. “Warwick to Present on Historic Poynor Chairs at Brentwood Library,” Williamson Herald, August 23, 2016. The census of 1860 also lists Poynor as a free man.11. The Williamson County Historical Society has published more than one journal volume which includes personal stories from various Poynors, alongside assessments of Poynor’s woodworking by Rick Warwick.12. Williamson County public historian Thelma Battles has been researching African American families and giving talks to share her findings for decades. Battles pieces together any connective tissue she turns up, telling intergenerational stories with vintage photographs and documents. She educates the public about her findings, including contacting families of the people whose stories she finds. In her work, she highlights the fact that “African Americans were constantly bought, sold, and transported, and forced to live in places not of their choosing.” See “Coming and Going,” African American Photo Exhibit (2015), February 23, 2015, accessed October 4, 2021, http://archive.org/details/Coming_and_Going_African-American_Photo_Exhibit_2015.13. Lester C. Lamon, Blacks in Tennessee, 1791–1970 (Knoxville: Tennessee Three Star Books, published in cooperation with the Tennessee Historical Commission [by] the University of Tennessee Press, 1981), 33.14. Lamon, Blacks in Tennessee.15. Alex Hubbard, “Forbes Ranks Williamson County in Top 10 Richest Counties in U.S.,” Tennessean, November 20, 2017.16. Tori Keafer, “FrankTown Draws Attention to ‘Housing Crisis’ in Franklin,” Williamson Herald, April 22, 2021, accessed October 16, 2021, http://www.williamsonherald.com/communities/franktown-draws-attention-to-housing-crisis-in-franklin/article_6ef27c90-a3ab-11eb-abec-4bd38edc1564.html.17. Jill Lawrence, “Values, Points of View Separate Towns — and Nation,” USA Today, February 18, 2002. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2002/02/18/divided-nation.html; https://www.geocities.ws/queermontclair/QMNewsletter202.html.18. “A Century of Chairmakers 1850–1950,” Williamson County Historical Society Journal, no. 22 (1991): 2.19. Rick Warwick: “Even after years of familiarizing myself with the work of Dick Poynor, I am still puzzled by the similarity of his work and that of Benjamin Waddey of Bethesda, Robert Baker of Bakertown and at least one other yet to be identified craftsman in the area. This puzzle has enlarged my study from southwestern Williamson County to the northern edge of Maury and Hickman counties.” And yet he expresses confidence in identifying chairs as having been made by Poynor. Similar fingerprints still differ notably.20. A lathe holds and rotates the piece to be shaped (in this case, wood), so that a craftsperson can hold a cutting tool and shave the wood down into a perfect cylinder, or a more complex finial.21. The Highland Woodworker - Episode 29.22. My thanks to MACR student Kate Hawes for pointing me toward the extensive research and woodworking of J.A. Alexander on the subject of green woodworking and slat-back chairs.